There’s much to learn and explore. You can start with the background pages or jump straight to the aviation heritage trail – ten of the best aviation related places in the county to visit. Just follow the links.

During World War Two, approximately four million operational flights were made over Cambridgeshire by bombers in 1944 alone; with a further two million flights involving a huge variety of other aircraft types. Six million flights a year.

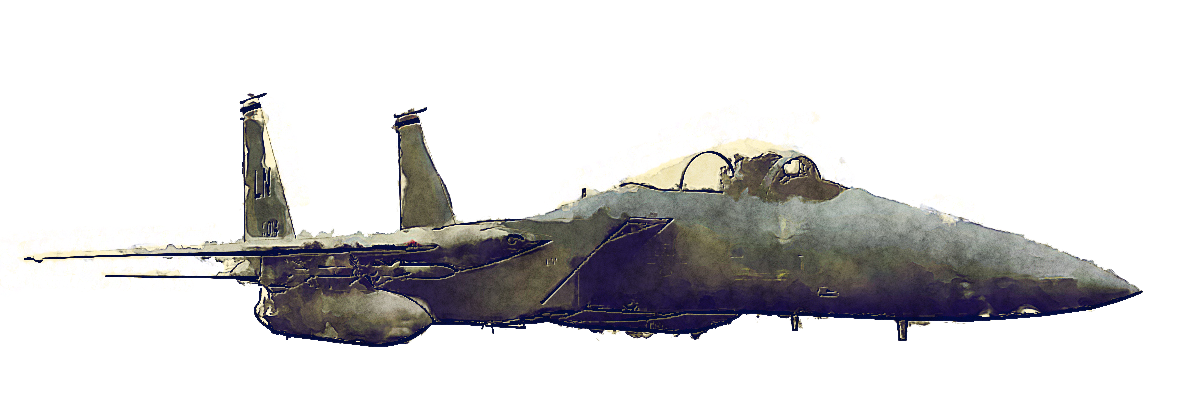

Even today, there are thought to be approximately 500,000 flights over the county every year. This total is made up of a huge range of different aircraft types – from commercial helicopters and private propeller-engined aircraft, through military jets such as US Air Force Europe (USAFE) KC135 Tankers and F15 Strike Eagles, to long-range commercial Boeing 777s and Airbus A380s overflying the county on their way to and from the USA.

Wherever you start, exploring Cambridgeshire’s aviation heritage is a fascinating, involving and often very surprising journey.

Aircrew in full flying kit walking beneath the nose of Short Stirling Mark I, N3676 ‘S’, of 1651 Heavy Conversion Unit at Waterbeach while the ground crew run up the engines. The photograph was taken in 1942 by Charles E Brown – a superb aviation photographer who made full use of colour film when photographing on the ground or in the air.

One of the most iconic images of the Battle of Britain. A 19 Squadron Spitfire is being re-armed at RAF Fowlmere by Armourer Fred Roberts. The pilot is Sergeant BJ Jennings and the buildings of Manor Farm can be seen in the background. Fowlmere is very near to RAF Duxford – one of the places featured on our Aviation Heritage Trail.

Avro Lancaster Mk II, 115 Squadron, RAF, Witchford, January 1944

McD F15c Eagle – 48th Fighter Wing USAFE, above Duxford, March 2016

Supermarine Spitfire Mk Ia – 19 Squadron RAF, Fowlmere, September 1940

Airbus A320-200, WizzAir, above Steeple Morden, May 2012

Cambridge City Cemetery. There are four Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) plots collectively containing over 1,000 graves of those killed during World Wars One and Two and shortly thereafter. Most of those buried here were members of the Royal Air Force (RAF), Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF).

Believed to have been taken on 26 March 1943, this photograph shows a bulldozer spreading bricks from bombed buildings, probably in London’s East End, as hardcore for the runways at RAF Witchford. These bricks are still, to this day, coming to the surface of the surrounding fields, even though the runways themselves have mostly disappeared.

Vickers-Armstrong Super VC10, BOAC/CUNARD, Duxford, April 1980

Royal Aircraft Factory FE2b – 75 (HD) Squadron RFC, Little Downham, May 1916