Contents

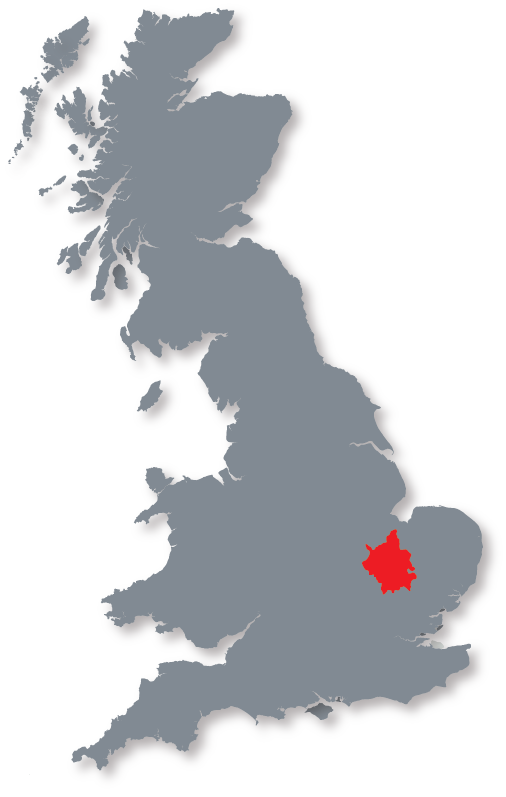

ContentsCambridgeshire is a county in the East of England. Cambridge is the county town and is most famously known as a University. The county has expanded over the years, taking in smaller areas deemed administratively unsuitable to remain on their own. These include the Isle of Ely and, confusingly, Huntingdonshire. Confusing because the former independent county area is still called that.

Cambridgeshire is approximately 1,170 square miles (3,000km) in size and has a population of approximately 650,000 people. The main towns are Cambridge, Huntingdon, St Ives, Ely and Wisbech. (Confusingly – that word again – Ely is technically a city because of its cathedral).

Geographically, the County is mostly flat. The highest point, Great Chishill, is 480 feet above sea level while the lowest, Holme Fen, is 9 feet below sea level. (This also happens to be the UK’s lowest point). It was this flatness and the County’s proximity to London and the South-East of England, as well as continental Europe, that has made it an obvious location for both military and civilian airfields.

But Cambridgeshire’s aviation heritage is not just a matter of airfields. Far from it.

Prior to WW1, British aviation was in its infancy. Fields may have been used as occasional landing grounds for flying schools, but the evidence for such activity seems often so tenuous that there seems little point in making very much of the matter. However, there was one event that seems to be of justifiable importance to the history of aviation within the County.

This event was the construction of a monoplane by Alfred Grose and Neville Freary at Manor Park Farm, Oakington. The men were attempting to win a Daily Mail prize of £1,000, (approximately £100,000 at today’s prices), for the first all-British plane piloted by a Briton to fly a circular mile. In the event, they and their aircraft – the so-called Oakington Monoplane – didn’t win the prize.

In the normal way of things, all this would have disappeared into history by now. However, there is a wonderful website which gives a remarkable amount of information on the plane and the men who built it – complete with photographs and contemporary reports from the Cambridge Chronicle. Well worth a view. (http://www.oakingtonplane.co.uk).

World War One – Landing Grounds

World War One – Landing GroundsThese landing grounds were usually no more than requisitioned fields in widely dispersed locations – the official basis for the choice of locations having long since been lost to researchers. The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) temporarily parked both aircraft and tents for its personnel in these fields but constructed few buildings or permanent structures. In consequence, there is nothing left to see at these sites. They have largely returned to agriculture.

The landing grounds were most frequently used by RFC Home Defence (HD) squadrons. These were deployed to undertake aerial patrols, often at night, in the hope of intercepting German Zeppelin and Gotha bombers. It is fair to say that these patrols were undertaken without much hope of achieving successful interceptions and, in the light of results achieved, the RFC’s general pessimism was entirely justified. However, the lessons learned led eventually and directly to the development of radar as a means of accurately guiding fighters to their targets – which was the basis on which the Battle of Britain would be fought and won in the early years of World War Two.

The County’s WW1 Landing Ground sites are as follows, (current status, where known, as indicated):

Some of the County’s WW2 airfields were constructed before the war, (eg: Bassingbourn, Duxford, Upwood), and the remainder during it, (eg: Mepal, Waterbeach, Witchford). This fact usually signifies a substantial difference in building styles. Pre-war airfields were built to generally high standards. Hangars, accommodation and office blocks, maintenance stores were brick/concrete built and generally substantial structures. Wartime airfields were quickly and relatively cheaply built, not expected to last for very long, and so it’s somewhat surprising that anything at all still remains of them. But, in some cases, it does.

The County’s WW2 airfield sites are as follows, (current status, where known, as indicated):

As noted above, there are a number of relevant sites:

Alconbury, Bassingbourn, Duxford, Mepal, Molesworth, Oakington, Upwood, Warboys, Waterbeach, Wittering, Wyton

Essentially, these sites fall into two categories: sites used by RAF aircraft-based squadrons, either operationally or for training purposes; and sites used by Thor nuclear IRBM installations.

All the sites are based upon then-existing WW2 airfield sites – therefore the same conditions of access and visibility (or otherwise) of structures apply.

Cambridgeshire has two aviation-related cemeteries of national importance: Cambridge City Cemetery and Madingley American Military Cemetery. Both these cemeteries contain large numbers of aviation-related service personnel who died during WW2. There are also a number of RAF-related plots in smaller cemeteries across the County. In some instances, the plots are large enough to be maintained by the CWGC. Otherwise, graves stand in small groups or on their own – most commonly because the individual(s) concerned may have died somewhere else but he or she was originally from that particular town or village.

In passing, it’s interesting to note that the arrangements for the burial of service casualties during WW2 are now entirely opaque. There is no means of understanding why, for example, an individual originally from, say, Birmingham is buried in Cambridge. In some instances, it is possible to make an informed guess. Lancaster bombers carried a crew of seven and in some cases it was decided – by whom is not clear – that all seven men should be buried together. It’s also the case that – for obvious reasons – the bodies of service personnel from Australia, New Zealand, Canada and elsewhere could not be returned to their home countries during wartime.

But, still, it’s probably true to say that the majority of British graves in Cambridge City Cemetery are of men and women who had little or even no connection with Cambridge itself. The reverse is also true – that there are many graves situated all over the country of individuals who were originally from Cambridge.

There are four service-related plots in the cemetery, containing over 1,000 graves. By far the biggest of these plots is largely given over to British and Commonwealth RAF casualties. This was one of a number of large RAF regional plots/cemeteries established during the war, (the others being Brookwood, Harrogate, Oxford and Chester).

Visitors to the cemetery always seem to appreciate the immaculate work of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) in maintaining the graves and their surroundings. There is an explanatory plaque providing background to all the plots and the CWGC’s work in them.

Maintained by a US Federal Government agency, the American Battle Monuments Commission, Madingley is the only WW2 US military cemetery in the UK. (Brookwood contains the graves of WW1 casualties). The site is on land originally donated by Cambridge University and contains approximately 3,900 graves, as well as a monument – the Tablets of The Missing – to more than 8,000 US service personnel who have no known graves. Many of these were crew members of aircraft which had taken off from bases in Cambridgeshire.

There is an impressive Chapel and Memorial building on the site. The Visitor Centre provides some background to some of the men buried in the cemetery, as well as displays of personal and equipment artifacts. All in all, the site is laid out and maintained to a very high standard.

The CWGC website provides a list of 151 separate locations across the county which have service personnel graves. Not all of these are associated with the RFC, RAF or other aerial services such as the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), or the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) but probably the majority are – because the Army and Navy conducted the vast majority of their operations abroad or at sea and those who died tend either to have no known graves or are buried as near as possible to where they fell.

The first location on the CWGC’s list for Cambridgeshire is Abington Pigotts – the Church of St Michael. There is one grave there – that of RAF Leading Aircraftman Arthur Tricker ,who died on 26 May 1946. The last location on the list is Woodditon – the Church of St Mary. There are three CWGC graves here, one being that of RAF Aircraftman 2nd Class William Pledger, who died on 18 September 1940. In between these two ends of the alphabetical scale, there are 149 other locations. Far too many to list here. However some of the larger locations are worth mentioning. (The total number of service graves is given in brackets, with the number of relevant aerial service graves following).

* These are gravestones which are the responsibility of the CWGC – even though they lie in a US military cemetery. The reason for the distinction is that 18 of these graves are mostly those of RAF, RAFVR and Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) personnel of American origin. The 19th grave is that of a Royal Armoured Corps Officer.

** This cemetery contains the graves of 37 people classed as ‘civilian war dead’. This classification invariably means that the individuals concerned died as a result of bombing or some other form of air raid.

During the early years of WW2, decoy sites were established across Cambridgeshire and many other counties. The intention was to mislead Luftwaffe bombers – which operated largely at night – into bombing country fields rather than airfields, cities and factories. The decoy sites were built and maintained by a secret Air Ministry unit – so secret, in fact, that it had no official name and was usually referred to as ‘Colonel Turner’s Department’.

Colonel John Turner was a twice-retired Army Engineering Officer who was once more brought back into service in order to preside over a programme which was cumulatively to build and operate approximately 790 decoy sites across the whole country. These sites varied in size and function, but nearly all of them were designed to persuade night-time Luftwaffe bomber pilots and bomb aimers that they were looking down at a real city or airfield.

Sites were placed in locations likely to be overflown by bombers on their way to their intended targets. Fake aircraft were constructed at places like Shepperton Studios and transported to equally fake airfields. Decoy sites simulated airfield lights or cities on fire. In daylight, such deceptions were very hard to achieve. But at night, all accounts indicate that they were remarkably realistic. This meant that a fairly substantial tonnage of Luftwaffe bombs was unloaded where it caused no damage to anyone or anything.

Little now remains of these sites. Most of the structures were anyway flimsy and extremely rudimentary – no more than pipes to carry fuel and baskets/braziers in which material was burnt. There were also arrays of lights designed to simulate runway lighting systems. The personnel operating these sites usually worked in a brick-built bunker and some of these still survive.

Sites were categorized according to their purpose. Colonel Turner understood that simply lighting the same type of fire, or switching on the same row of lightbulbs, in many different locations would not fool anyone into believing that they were seeing what they were supposed to be seeing. Therefore, there were many different types of lighting effect developed and in Cambridgeshire, five individual categories of sites were deployed, (some being combined for maximum effect and/or because of a shortage of suitable sites).

The following list is understood to be a reasonably accurate list of all known decoys sites in the County. It can be assumed that at least some of them are visible – either from a road or a public footpath. However, anyone hoping to catch sight of a defunct fire brazier, or perhaps a line of piping, is likely to be severely disappointed. (Although it is possible to look at some sites on Google Earth and this view sometimes reveals apparently random craters in otherwise perfectly flat fields).

It’s fair to say that Cambridgeshire is awash with war memorials of all shapes and sizes. The website roll-of-honour.com lists 259 memorials for Cambridgeshire and a further 78 for Huntingdonshire. This is not, almost certainly, the definitive total of actual memorials and the list does not include, for example, incidental memorials such as village signs which have some sort of depiction of an aircraft as part of their design, (eg: Bassingbourn, Conington, Bourn, Litlington, Steeple Morden); or streets named after something aerial, (eg: Lancaster Way in Witchford).

Leaving aside those memorials devoted to the Boer War and other conflicts, and those memorials which exclusively list the names of those who died in WW1, there are basically three categories of WW2 memorial.

The classic British war memorial is a somewhat weatherbeaten Celtic-style wheel stone cross situated somewhere in a churchyard or perhaps on the village green. Around the base of the cross, the names of those who died in WW1 are inscribed. Later additions for WW2 – usually much fewer in number – and other conflicts are added on any available spare space. The style is name and initials only. Generally, no ranks or unit names are given.

None of this helps anyone trying to understand who all these people were or how and when they died. The website roll-of-honour.com has done an excellent job of transcribing names on hundred of memorials and providing, where possible, service and other details for each individuals.

Separately, there are often commemorative plaques inside churches or institutions. These tend to commemorate individuals or particular groups who came from, or worked in, the same place. Cambridge University, for example, has a number of such memorials in its colleges.

In conclusion, it’s fair to say that very few of these memorials are on such a grand or distinctive scale that it would be worth recommending them as places to warrant a specific journey. And, of course, the names given can be those of men who died anywhere in the world. For example, many men of the Cambridgeshire Regiment died in Singapore or in Japanese Prisoner of War camps. Others have no known grave and their names are also recorded on the Runnymede Memorial.

What follows is a representative selection only. Memorial plaques in churches are not included.

RAF squadrons were rarely stationed wholly and exclusively in one location for the entire duration of the war. They were also composed of men who came from all over the country or much further afield. Therefore such memorials generally take a broad view of a squadron’s activities, encompassing anything and everything it may have done. Still, better that a squadron is commemorated in any way than largely forgotten.

Notable memorials in this category include:

This is a fairly problematic subject, not just because every crash site is potentially a war grave. There is also the general undesirability of anyone with a metal detector wandering about the countryside, mostly on private land and without permission, in search of digging opportunities for war souvenirs.

Equally, crashed aircraft have their own tale to tell. So describing crash sites within the County does provide another dimension to the overall story of the county’s aviation heritage. There is, at the very least, the matter of how every aircraft came to crash in the first place.

For example, on the night of 18/19 April 1944, Lancaster LL667 from 115 Squadron was returning from an attack on the railway marshalling yards at Rouen. It was approximately 02.00 hours and the Lancaster was in the final stages of its landing at Witchford when it was intercepted by a Luftwaffe intruder aircraft and shot down. The Lancaster crashed in a field just by West Fen Road, Coveney. None of the crew of seven survived. In 1995, the remains of the aircraft were excavated and three of the aircraft’s four Bristol Hercules XVI engines were recovered. One of these, the starboard inner, was thoroughly cleaned and now forms the centerpiece of the display at RAF Witchford Museum.

In passing, it’s interesting to note that two of the crew were subsequently buried in Cambridge City Cemetery. One of them was wireless operator Ernest Kerwin, from Wakefield, Yorkshire. The other was the bomb aimer, an American, Arnold Feldman, from Norwalk, Connecticut, and serving with the RCAF. Approximately half an hour after their Lancaster had been shot down, another 115 Squadron Lancaster, LL867, passed directly over the burning remains of LL667 and was itself shot down by another Luftwaffe intruder. None of the crew on LL867 survived either and two of them, pilot Charlie Eddie and air gunner Henry Bennis, are also buried in Cambridge.

One writer has made a Cambridgeshire crash site the central aspect of an entire book. Jennie Gray wrote about her father, Joe, who was the sole survivor of a Lancaster crash in extremely poor weather just as it was about to land at Bourn. The book is Fire By Night and it is an exceptionally good read. The Lancaster was from 97 Squadron, based at Bourn, and the crash occurred on the night of 16/17 December 1943. This became known as ‘Black Thursday’, because 70 returning Bomber Command aircraft crashed on this night as a direct result of the bad weather. Five of these aircraft were from 97 Squadron – the biggest single night’s loss suffered by the squadron during the war.

All these examples are, almost by chance, very well-documented. The reasons for, and locations of, a whole host of other aircraft crashes in the County are now entirely lost to view. Wartime official records were notoriously poor at documenting crash sites. Recovery teams salvaged bodies and any usable equipment, and then mostly bulldozed what was left into whatever crater had been formed in the first place. Over the years, bits and pieces have risen to the surface in various places.

The closest to a comprehensive list appears in the book War-Torn Skies of Great Britain: Cambridgeshire. The author acknowledges that his list is itself not complete. Nevertheless, he lists 166 incidents occurring between 12 August 1938 and 8 November 1945. Most of the incidents resulted in fatalities.

What follows, therefore, is a brief representative list of three incidents and locations.

On 19 July 1944, a B17G Flying Fortress from the 612th Bomb Squadron crashed within the airfield’s perimeter after the pilot had taken 11 friends along for a joyride. No-one on board the aircraft survived and one of the airfield’s accommodation blocks was completely destroyed.

This National Trust (NT) property has a sign indicating that a Meteor fighter from Waterbeach crashed on the site during the 1950s. No confirmation of this crash has yet been obtained from official records, nor has any wreckage been found. Even the NT admits that the event may be apocryphal.

The following comes from an excellent website, (wcnhistory.org.uk): A horrific accident occurred at West Wickham on 4 July 1943, when a Stirling, BF504, which had just taken off, side-slipped from about 500 feet, hit the ground and exploded. Two airmen sitting outside the temporary Sick Quarters drinking tea after their midday meal saw it happen and raced to the scene, only about 200 years away. Screaming aircrew, their clothes alight, were rolling on the ground in agony, and the two airmen rushed from one to another putting out the flames.

Two died there and then; the other five were put in the ambulance which left in great haste for the RAF Hospital at Ely, the only facility equipped to deal with serious burns. On the way, the ambulance was held up at a railway level crossing, but when the circumstances were explained, the crossing keeper stopped a train and let the ambulance through. Three more of the aircrew had died by the time the ambulance reached the hospital, and the remaining two were carefully off-loaded. The two rescuers had suffered burnt hands, which were treated by the ward sister.

After an hour, the two men began their weary journey back to West Wickham, in the sad knowledge that the last aircrew had just died. Next day, one of the ambulance men was put on a charge for “taking an ambulance without proper authorisation”, and was awarded seven days ‘Confined to Barracks’.

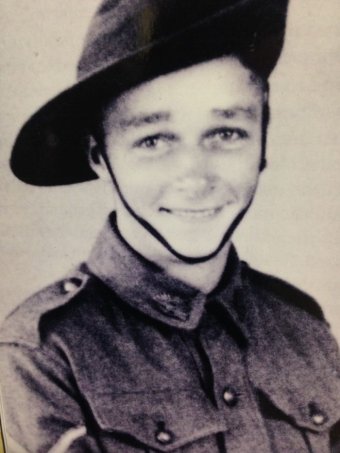

Finally, special mention must be made of an Australian pilot, Pilot Officer Jim Hocking, who was flying a Stirling bomber in July 1944 on a training flight when his aircraft engine caught fire. Jim ordered all his crew to bail out. He was about to follow them when he realised that the abandoned aircraft would have crashed into the town of March. Jim stayed at the controls and ensured that the aircraft crashed instead in nearby fields. In doing so, he lost his own life. Originally from Queensland, Australia, Jim was posthumously awarded the Star of Courage – Australia’s second highest award for bravery. A former student at his school, Joyce Milligan, had campaigned over many years for the decoration to be awarded in recognition of Jim’s outstanding bravery.

Finally, special mention must be made of an Australian pilot, Pilot Officer Jim Hocking, who was flying a Stirling bomber in July 1944 on a training flight when his aircraft engine caught fire. Jim ordered all his crew to bail out. He was about to follow them when he realised that the abandoned aircraft would have crashed into the town of March. Jim stayed at the controls and ensured that the aircraft crashed instead in nearby fields. In doing so, he lost his own life. Originally from Queensland, Australia, Jim was posthumously awarded the Star of Courage – Australia’s second highest award for bravery. A former student at his school, Joyce Milligan, had campaigned over many years for the decoration to be awarded in recognition of Jim’s outstanding bravery.

As an aside, there were also a number of Luftwaffe bombing attacks on the county during WW2 – some of which resulted in fatalities.

There were a number of Luftwaffe bombing attacks on the County during WW2 – some of which resulted in fatalities.

The first significant air raid on Cambridge was on the night of 19/20 June 1940. Ten people were killed and twelve injured when two bombs fell on Vicarage Terrace.

The Perse School in Hills Road was severely damaged by bombs on the night of 16/17 January 1941. 200 incendiaries are believed to have fallen in the area.

The last attack on the city is believed to have taken place on the night of 5/6 November 1943 – when a V1 was heard to explode. Throughout WW2, five ‘doodlebugs’ were believed to have landed in the county, (at Melbourn, Burwell, Castle Camps, West Wicken and Heydon). There was only one V2 attack – at Fulbourn in 1944.

Like many other historic British towns, Cambridge was attacked as a direct result of Hitler’s instruction to the Luftwaffe to undertake reprisal raids following an RAF attack early in WW2 on the historic German town of Rostock.

There were a number of attacks on the airfield. Probably the heaviest was on 16 August 1940 – when 220 bombs were recorded as having fallen in the area.

The church was badly damaged during an attack in 1940.