The British Airliner Collection is the collective name for a superb array of thirteen British civil aircraft on display at Duxford. These aircraft are owned and maintained by the Duxford Aviation Society – a registered charity and on-site partner of IWM Duxford.

If you want to understand the development of British civil aviation in the years after World War Two, leading right up to the 1980s, then you have to visit this Collection. Better still, the interiors of these aircraft are, almost literally, time capsules. You can see how people travelled. Not so different, you might think, from how everyone travels these days.

If you want to understand the development of British civil aviation in the years after World War Two, leading right up to the 1980s, then you have to visit this Collection. Better still, the interiors of these aircraft are, almost literally, time capsules. You can see how people travelled. Not so different, you might think, from how everyone travels these days.

But there are differences. Some of them are quite surprising. For example, civil aircraft then were generally smaller than they are now. But they tend to feel more spacious. The fuselage windows were sometimes bigger than they are now. As were the seats. Flying anywhere, on holiday or for business, was not the mass market business it has now become. An airline ticket was comparatively expensive and so people who bought these tickets expected to fly in some comfort. Airlines could generally afford to provide it.

For the lucky few, there was Concorde. This aircraft offered its own form of luxury: time-saving. In just three or so hours, you could be in New York. In fact, you could comfortably go there and come back to London in a day. It’s still possible to do this, of course, but the journey would take much longer and would make for a very long and tiring day indeed.

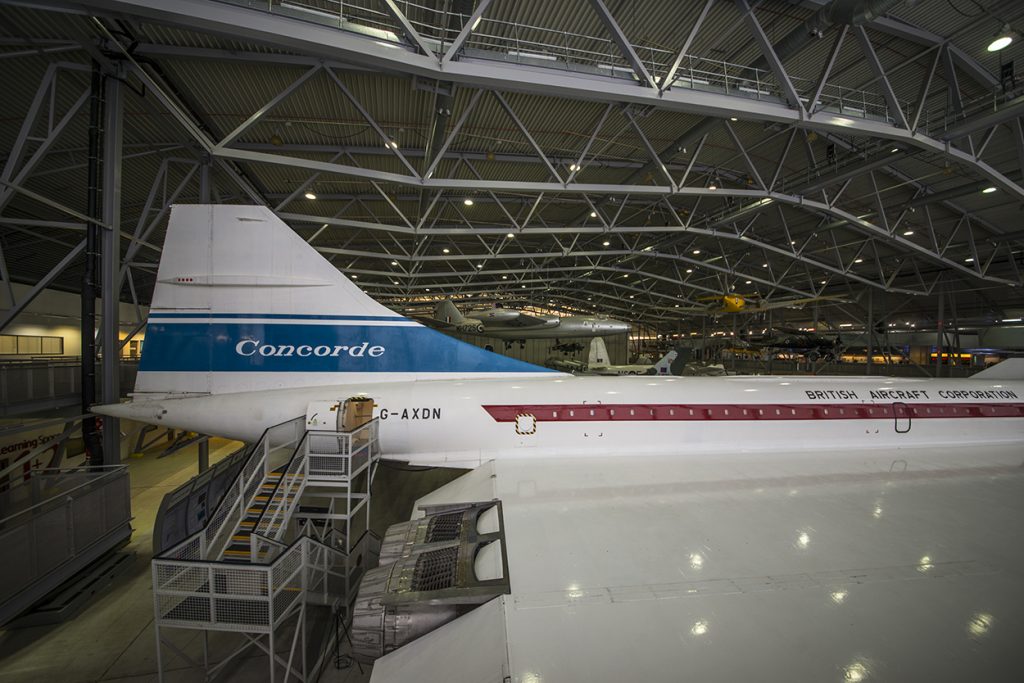

The Duxford Aviation Society has put Concorde 101, (the third Concorde to be built), on display in the AirSpace building. Climb the steps at the rear of the aircraft and enter the aircraft cabin. The first thing that strikes you is how small the space is. There is room for only two rows of seats, two abreast.

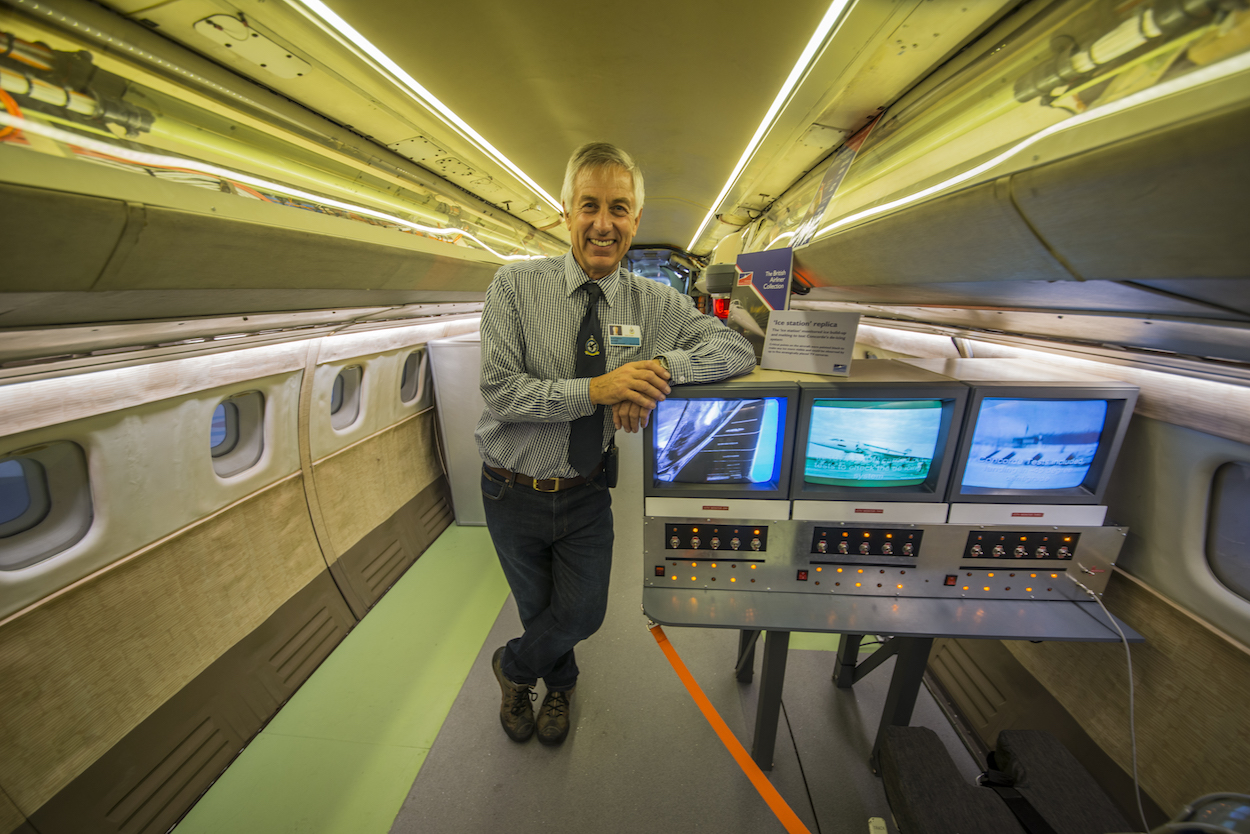

This particular Concorde was used only for testing purposes. There are no passenger seats inside. Instead, there is an array of test equipment – simulating the equipment used to develop the supersonic performance of the aircraft’s four Rolls Royce/SNECMA Olympus engines and to test the aircraft’s de-icing system. Indeed, it was this very aircraft which, back in March 1974, climbed to an altitude of 63,700 ft and then achieved a speed of 1,450 mph – the highest speed ever recorded by any Concorde.

This particular Concorde was used only for testing purposes. There are no passenger seats inside. Instead, there is an array of test equipment – simulating the equipment used to develop the supersonic performance of the aircraft’s four Rolls Royce/SNECMA Olympus engines and to test the aircraft’s de-icing system. Indeed, it was this very aircraft which, back in March 1974, climbed to an altitude of 63,700 ft and then achieved a speed of 1,450 mph – the highest speed ever recorded by any Concorde.

Hardly surprising, in view of Concorde’s fame, that this aircraft has become the most popular single exhibit at Duxford. An estimated six million people have walked through it.

Elsewhere in the AirSpace building is another of the Collection’s aircraft – a de Havilland Comet 4. Concorde may have provided the fastest journey across the Atlantic, but this particular Comet 4 had the honour of operating the very first scheduled jet airliner service between New York and London. It took place on 4th October 1958 and, for the record, the journey took 6 hours and 11 minutes. Not so impressive these days, perhaps, but a revelation in the late 1950s.

Inside this aircraft, you can see how the passengers travelled. For the New York service, there were just 16 deluxe seats and 32 first-class seats. This number eventually increased to a maximum of approximately 100 seats on other routes but, by today’s standards, it remains small. And it was this fact, quite apart from two disastrous crashes in 1954, which ultimately ensured the Comet’s failure as a commercial airliner.

Put simply, the American Boeing 707, introduced into service just 22 days after that record-making flight between London and New York, flew further and carried more passengers. The economics of the airline industry determined that there would only ever be one winner of this particular contest.

Concorde is flanked by two of the earliest airliners to enter service after World War Two. One is the Avro York, developed from the immortal Lancaster. This particular aircraft served with the now-defunct independent airline Dan-Air but was originally built as a transport aircraft for the RAF and for a time was based at Oakington with 242 Squadron. It took part in the Berlin Airlift and carried the 100,000th ton of supplies into the city. The other is the only surviving Handley Page Hermes, descended from the wartime Halifax bomber and one of the earliest pressurised airliners. Suspended from the roof above the Comet is the Collection’s de Havilland Dove, the first British Airliner built after the War.

Leaving the AirSpace building, walking past the first of the hangars and beyond the Control Tower, you will see a line of civil aircraft. These all belong to the Duxford Aviation Society. They are:

Quite apart from being a fantastic collection of civil airliners situated in close proximity, many of these aircraft have some interesting claims to fame.

This Bristol Britannia, for example, is now painted in Monarch Airlines colours but it was first used by the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) in 1959. Deployed on long-range routes, this particular aircraft inaugurated BOAC’s first round-the-world service. It flew from London to New York, San Francisco, Honolulu and Wake Island in the Pacific, before eventually reaching Tokyo. (The remaining part of the journey to London being taken onwards by a Comet 4).

This Bristol Britannia, for example, is now painted in Monarch Airlines colours but it was first used by the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) in 1959. Deployed on long-range routes, this particular aircraft inaugurated BOAC’s first round-the-world service. It flew from London to New York, San Francisco, Honolulu and Wake Island in the Pacific, before eventually reaching Tokyo. (The remaining part of the journey to London being taken onwards by a Comet 4).

This Britannia was subsequently sold to the now-defunct airline British Eagle and further sold to also now-defunct Monarch Airlines in 1969. Its very last flight was to Duxford, in June 1975, when it completed its last of a total of 10,760 landings made during its lifetime.

An impressive number, but one dwarfed by that of the BAC 1-11. This aircraft first flew in January 1969. It had been ordered by British European Airways (BEA) for use on its short-haul services in Europe. When BEA became British Airways in 1972, the aircraft was repainted in new colours and named County of Dorset – as it is today. The aircraft type was very reliable and something of a commercial success, with 244 sold to customers across the world. Eventually, this particular example was retired and subsequently flown to Duxford. It had flown a total of 40,279 hours over the course of its life and it had made a remarkable 45,450 landings.

An impressive number, but one dwarfed by that of the BAC 1-11. This aircraft first flew in January 1969. It had been ordered by British European Airways (BEA) for use on its short-haul services in Europe. When BEA became British Airways in 1972, the aircraft was repainted in new colours and named County of Dorset – as it is today. The aircraft type was very reliable and something of a commercial success, with 244 sold to customers across the world. Eventually, this particular example was retired and subsequently flown to Duxford. It had flown a total of 40,279 hours over the course of its life and it had made a remarkable 45,450 landings.

The Vickers Viscount was the world’s first turboprop-powered airliner; its first flight being undertaken in December 1952. This particular example is the second aircraft of its type to be produced and now the oldest surviving example. It was first used by BEA and subsequently by a number of British airlines, before eventually completing its last flight in April 1972. At first it was put on display in Liverpool but it was subsequently dismantled and moved to Duxford in 1976. The aircraft had flown almost 7 million miles during its lifetime, carrying an estimated 800,000 passengers, and made 25,938 landings.

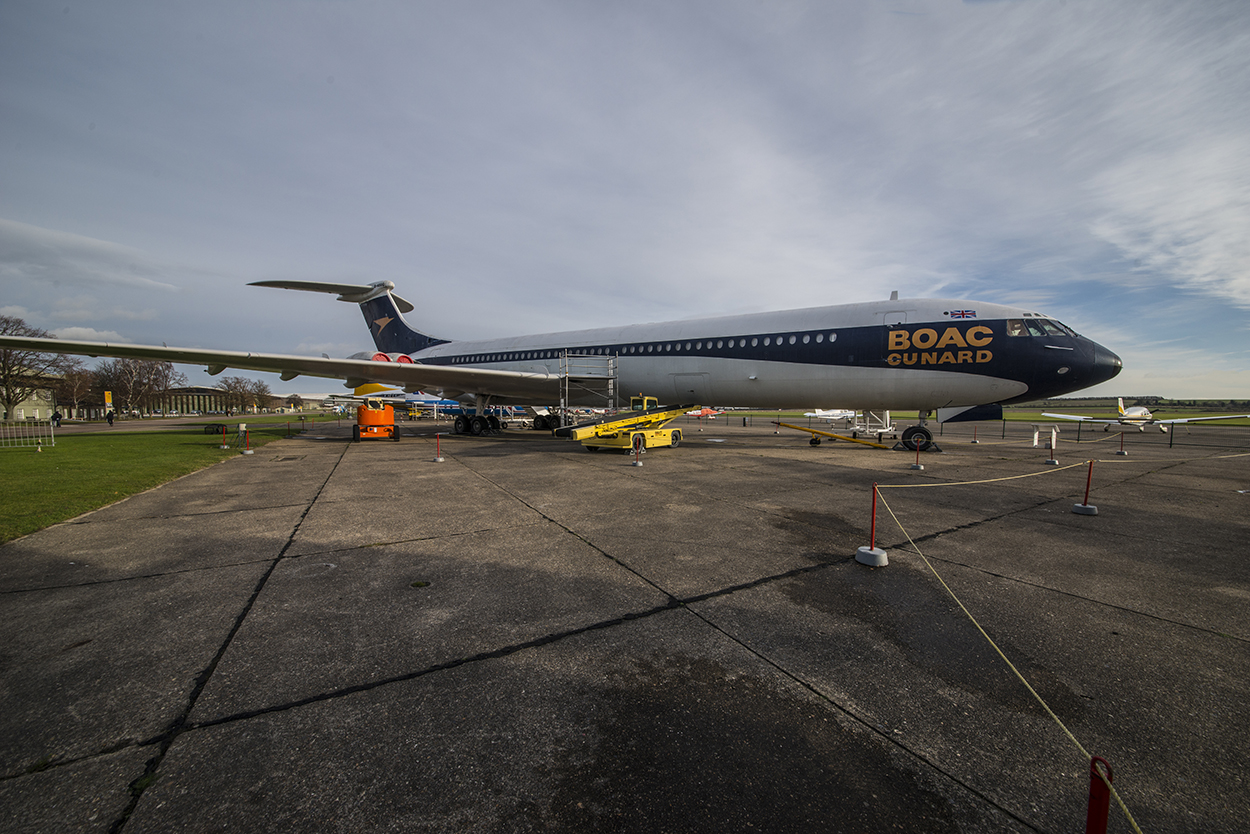

This Vickers Super VC10 first flew on 1 January 1965. Its last commercial flight was on 22 October 1979. A firm favourite with passengers, because the engines were situated at the rear of the fuselage and therefore made the aircraft cabin much quieter during flight than the cabins of most other types, this aircraft was one of just 17 built for BOAC. (Not including a further 12 standard VC10s). There had been high hopes for the commercial success of the type but they entirely failed to materialise. The launch customer, BOAC, had specified the aircraft precisely for its own requirements, resulting in something which was more expensive to operate than rivals such as the ever-durable Boeing 707. Despite the VC10’s undeniably elegant appearance, and passengers’ appreciation of its quietness and comfort, the economics of the airline industry once more triumphed.

This Vickers Super VC10 first flew on 1 January 1965. Its last commercial flight was on 22 October 1979. A firm favourite with passengers, because the engines were situated at the rear of the fuselage and therefore made the aircraft cabin much quieter during flight than the cabins of most other types, this aircraft was one of just 17 built for BOAC. (Not including a further 12 standard VC10s). There had been high hopes for the commercial success of the type but they entirely failed to materialise. The launch customer, BOAC, had specified the aircraft precisely for its own requirements, resulting in something which was more expensive to operate than rivals such as the ever-durable Boeing 707. Despite the VC10’s undeniably elegant appearance, and passengers’ appreciation of its quietness and comfort, the economics of the airline industry once more triumphed.

The Hawker Siddeley Trident 2E was one of a family of similar aircraft (including the Trident 1 and Trident 3) which represented a better commercial bet by its makers, the British Aircraft Corporation. The Trident 2 Series was the first airliner type equipped with blind landing equipment. Essentially, and probably at the cost of nervous passengers being terrified at the prospect, the aircraft could land itself should its pilot decide that visibility was too low for a normal landing. This was a major advantage whenever fog enveloped British and European airports.

This particular Trident 2E was delivered to BEA in June 1968. It was subsequently sold to Cyprus Airways in June 1972. Nicosia Airport is not renowned for foggy conditions, but it was here that this Trident suffered its worst mishap. When Turkish forces invaded Northern Cyprus in July 1974, the aircraft was parked at the airport and caught in crossfire. Along with other aircraft, it had several bullet holes but, fortunately, no structural damage. British Airways repaired the aircraft and began using it again. Its last flight was to Duxford, on 13 June 1982. During its operational lifetime, the aircraft had flown a total of 21,642 hours and made 11,726 landings. The number of bullet holes is not known.

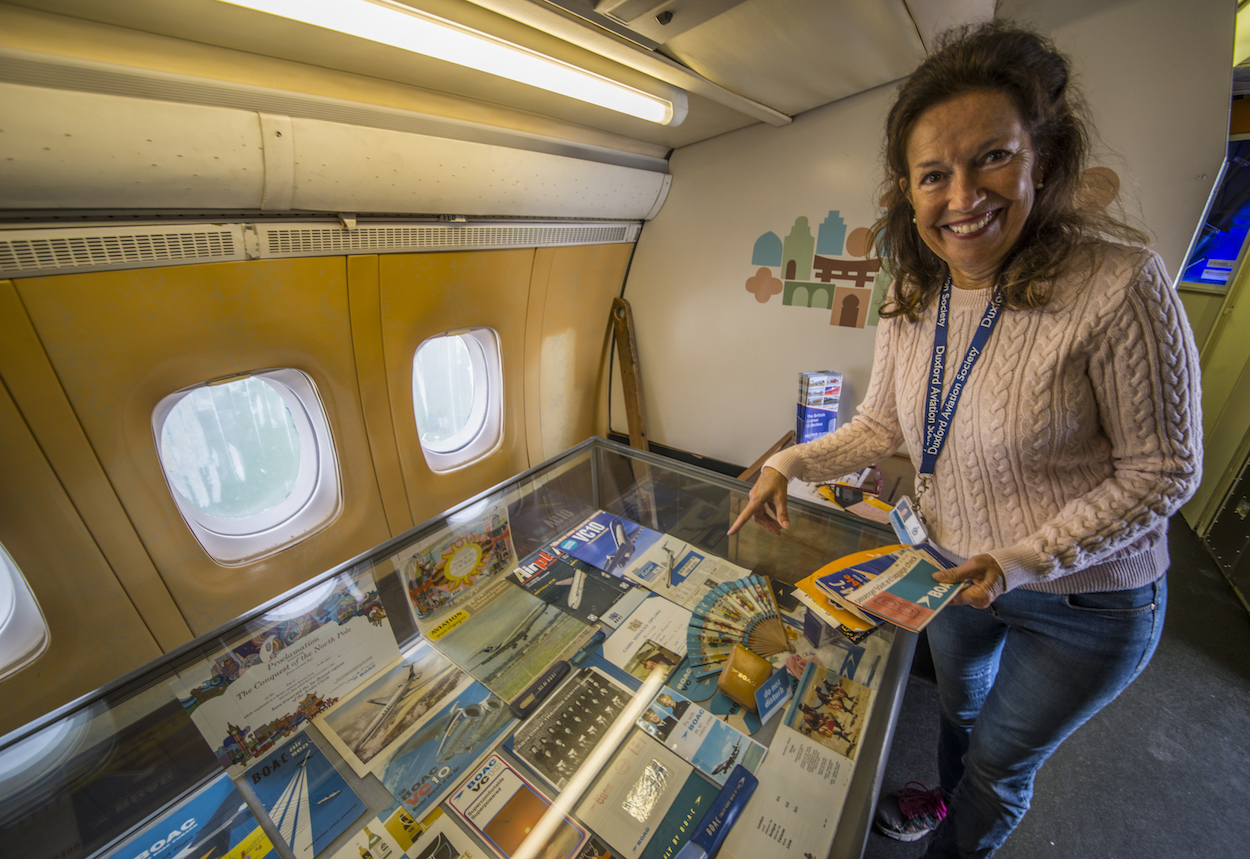

Seeing all these aircraft on the ground and up close, with the kind of access that is now impossible at today’s civil airports, is a very good reason for visiting the collection. Better still, it is sometimes possible to go inside most of the aircraft and take a good look around. Access is only provided by the Duxford Aviation Society and entirely dependent upon there being sufficient volunteer staff available. So if you want to see inside, say, the Super VC10; it’s very strongly advisable to phone the Society first and check when it will be open. Alternatively, it’s sometimes possible to make an arrangement for a particular time and date.

Seeing all these aircraft on the ground and up close, with the kind of access that is now impossible at today’s civil airports, is a very good reason for visiting the collection. Better still, it is sometimes possible to go inside most of the aircraft and take a good look around. Access is only provided by the Duxford Aviation Society and entirely dependent upon there being sufficient volunteer staff available. So if you want to see inside, say, the Super VC10; it’s very strongly advisable to phone the Society first and check when it will be open. Alternatively, it’s sometimes possible to make an arrangement for a particular time and date.

Entry to all the Society’s aircraft is entirely free except on Duxford’s Air Show days when, for a small charge, you can visit all the airliners, (except the Dove).

The Duxford Aviation Society is always looking for volunteers. For over 40 years, they have been responsible for maintaining these beautiful aircraft and presenting them to the public. If you have particular skill and experience which you think might be useful, or if you would just like to help in some way, the Society would be delighted to hear from you. Contact details are given below.

The Duxford Aviation Society is always looking for volunteers. For over 40 years, they have been responsible for maintaining these beautiful aircraft and presenting them to the public. If you have particular skill and experience which you think might be useful, or if you would just like to help in some way, the Society would be delighted to hear from you. Contact details are given below.

E-mail: enquiries@das.org.uk

Telephone: 01223 836 593

For more information on the Society and its work, visit www.das.org.uk